Iran is an incredibly interesting and complicated country. Located between Afghanistan and Iraq and slightly smaller than Alaska, Iran is home to more than 82 million people and has many rich cultures, a vibrant cinema, a diverse economy, and has been under attack and threat of attack by the United States for over sixty years. Below are a few helpful readings we at History Is A Weapon thought we could share with people interested in learning more about U.S. foreign policy. Please do not mistake these brief readings for a comprehensive history of U.S.-Iranian relations, but everyone should know the facts below. Please Share.

Iran is an incredibly interesting and complicated country. Located between Afghanistan and Iraq and slightly smaller than Alaska, Iran is home to more than 82 million people and has many rich cultures, a vibrant cinema, a diverse economy, and has been under attack and threat of attack by the United States for over sixty years. Below are a few helpful readings we at History Is A Weapon thought we could share with people interested in learning more about U.S. foreign policy. Please do not mistake these brief readings for a comprehensive history of U.S.-Iranian relations, but everyone should know the facts below. Please Share.

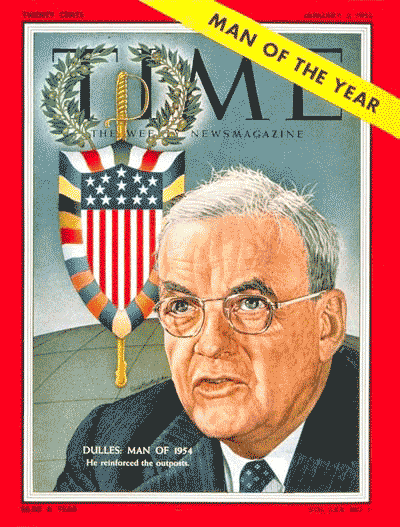

During the 1952 presidential campaign, [Secretary of State John Foster] Dulles made a series of speeches accusing the Truman administration of weakness in the face of Communist advances. He promised that a Republican White House would "roll back" Communism by securing the "liberation" of nations that had fallen victim to its "despotism and godless terrorism." As soon as the election was won, he began searching for a place where the United States could strike a blow against this scourge. Before he had even taken office, like a messenger from heaven, a senior British intelligence officer arrived in Washington carrying a proposal that perfectly fit Dulles's needs.

BRITAIN WAS AT THAT MOMENT FACING A GRAVE CHALLENGE. ITS ABILITY TO project military power, fuel its industries, and give its citizens a high standard of living depended largely on the oil it extracted from Iran. Since 1901 a single corporation, the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, principally owned by the British government, had held a monopoly on the extraction, refining, and sale of Iranian oil. Anglo-Iranian's grossly unequal contract, negotiated with a corrupt monarch, required it to pay Iran just 16 percent of the money it earned from selling the country's oil. It probably paid even less than that, but the truth was never known, since no outsider was permitted to audit its books. Anglo-Iranian made more profit in 1950 alone than it had paid Iran in royalties over the previous half century.

In the years after World War II, the currents of nationalism and anticolonialism surged across Asia, Africa, and Latin America. They carried an outspokenly idealistic Iranian, Mohammad Mossadegh, to power in the spring of 1951. Prime Minister Mossadegh embodied the cause that had become his country's obsession. He was determined to expel the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, nationalize the oil industry, and use the money it generated to develop Iran.

Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh of Iran signs the guest book while visiting Mount Vernon in the fall of 1951.

Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh of Iran signs the guest book while visiting Mount Vernon in the fall of 1951.Mossadegh, a European-educated aristocrat who was sixty-nine years old when he came to power, believed passionately in two causes: nationalism and democracy. In Iran, nationalism meant taking control of the country's oil resources. Democracy meant concentrating political power in the elected parliament and prime minister, rather than in the monarch, Mohammad Reza Shah. With the former project, Mossadegh turned Britain into an enemy, and with the latter he alienated the shah.

In the spring of 1951, both houses of the Iranian parliament voted unanimously to nationalize the oil industry. It was an epochal moment, and the entire nation celebrated. "All of Iran's misery, wretchedness, lawlessness and corruption over the last fifty years has been caused by oil and the extortions of the oil company," one radio commentator declared.

Under the nationalization law, Iran agreed to compensate Britain for the money it had spent building its wells and refinery, although any impartial arbitrator would probably have concluded that given the amount of profit the British had made in Iran over the years, Iran's debt would be less than nil. Mossadegh loved to point out that the British had themselves recently nationalized their coal and steel industries. He insisted that he was only trying to do what the British had done: turn their nation's wealth to its own benefit, and make reforms in order to prevent people from resorting to revolution. British diplomats in the Middle East were, of course, unmoved by this argument.

"We English have had hundreds of years of experience on how to treat the natives," one of them scoffed. "Socialism is all right back home, but out here you have to be the master."

Mossadegh's rise to power and parliament's vote to nationalize the oil industry thrilled Iranians but outraged British leaders. The idea that a backward country like Iran could rise up and deal them such a blow was so stunning as to be incomprehensible. They scornfully rejected suggestions that they offer to split their profits with Iran on a fifty-fifty basis, as American companies were doing in nearby countries. Instead they vowed to resist.

"Persian oil is of vital importance to our economy," Foreign Secretary Herbert Morrison declared. "We regard it as essential to do everything possible to prevent the Persians from getting away with a breach of their contractual obligations."

Over the next year, the British did just that. At various points they considered bribing Mossadegh, assassinating him, and launching a military invasion of Iran, a plan they might have carried out if President Truman and Secretary of State Dean Acheson had not become almost apoplectic on learning of it. The British sabotaged their own installations at Abadan in the hopes of convincing Mossadegh that he could not possibly run the oil industry without them; blockaded Iranian ports so no tankers could enter or leave; and appealed unsuccessfully to the United Nations Security Council and the International Court of Justice. Finally, they concluded that only one option was left. They resolved to organize a coup.

Britain had dominated Iran for generations, and during that time had suborned a variety of military officers, journalists, religious leaders, and others who could help overthrow a government if the need arose. Officials in London ordered their agents in Tehran to set a plot in motion. Before the British could strike their blow, however, Mossadegh discovered what they were planning. He did the only thing he could have done to protect himself and his government. On October 16, 1952, he ordered the British embassy shut and all its employees sent out of the country. Among them were the intelligence agents who were organizing the coup.

This left the British disarmed. Their covert operatives had been expelled from Iran, Truman's opposition made an invasion impossible, and world organizations refused to intervene. The British government faced the disorienting prospect of losing its most valuable foreign asset to a backward country led by a man they conSidered, according to various diplomatic cables, "wild," "fanatical," "absurd," "gangster-like" "completely unscrupulous," and "clearly imbalanced."

Modern Iran has produced few figures of Mossadegh's stature. On his mother's side he was descended from Persian royalty. His father came from a distinguished clan and was Iran's finance minister for more than twenty years. He studied in France and Switzerland, and became the first Iranian to win a doctorate in law from a European university. By the time he was elected prime minister, he had a lifetime of political experience behind him.

Mossadegh was also a highly emotional man. Tears rolled down his cheeks when he delivered speeches about Iran's poverty and misery. Several times he collapsed while addressing parliament, leading Newsweek to call him a "fainting fanatic." He suffered from many ailments, some physical and others of unknown cause, and had a disarming habit of receiving guests while lying in bed. His scrupulous honesty and intense parsimony-he used to peel two-ply tissues apart before using themmade him highly unusual in Middle Eastern politics and greatly endeared him to his people. In January 1952, Time named him man of the year, choosing him over Winston Churchill, Douglas MacArthur, Harry Truman, and Dwight Eisenhower. It called him an "obstinate opportunist" but also "the Iranian George Washington" and "the most world-renowned man his ancient race had produced for centuries."

Barely two weeks after Mossadegh shut the British embassy in Tehran, Americans went to the polls and elected Eisenhower as president. Soon after that, Eisenhower announced that Dulles would be his secretary of state. Suddenly the gloom that had enveloped the British government began to lift.

At that moment the chief of CIA operations in the Middle East, Kermit Roosevelt, happened to be passing through London on his way home from a visit to Iran. He met with several of his British counterparts, and they presented him with an extraordinary proposal. They wanted the CIA to carry out the coup in Iran that they themselves could no longer execute, and had already drawn up what Roosevelt called "a plan of battle."

What they had in mind was nothing less than the overthrow of Mossadegh. Furthermore, they saw no point in wasting time by delay. They wanted to start immediately. I had to explain that the project would require considerable clearance from my govemment and that I was not entirely sure what the results would be. As I told my British colleagues, we had, I felt sure, no chance to win approval from the outgoing administration of Truman and Acheson. The new Republicans, however, might be quite different.

British officials were so impatient to set the coup in motion that they decided to propose it at once, without even waiting for Eisenhower to be inaugurated. They sent one of their top intelligence agents, Christopher Montague Woodhouse, to Washington to present their case to Dulles. Woodhouse and other British officials realized that their argument—Mossadegh must be overthrown because he was nationalizing a British oil company—would not stir the Americans to action. They had to find another one. It took no deep thought to decide what it should be. Woodhouse told the Americans that Mossadegh was leading Iran toward Communism.

Under normal circumstances, this would be a difficult case to make. There was a Communist party in Iran, known as Tudeh, and like every other party in the country, it supported the oil nationalization project. Mossadegh, a convinced democrat, allowed Tudeh to function freely but never embraced its program. In fact, he abhorred Communist doctrine and rigorously excluded Communists from his government. The American diplomat in Tehran assigned to monitor Tudeh recognized all this, and reported to Washington that the party was "well-organized but not very powerful." Years later, an Iranian-American scholar conducted an exhaustive study of Tudeh's position in 1953, and concluded that "the type of coordinated cooperation and mutual reliance the Americans feared existed between Mossadegh and the Tudeh could not have existed."

The perceived Tudeh threat, as feared by the perpetrators of the coup, was not real. The party had neither the numbers, nor the popularity, nor a plan to take over state power with any hope of holding on to it .... This decision [to stage the coup] seems to have had little to do with on-theground realities and much to do with the ideological imperatives of the period: the Cold War.

Woodhouse gave Dulles the idea that he could portray Mossadegh's overthrow as a "rollback" of Communism. The State Department, however, did not have the capacity to overthrow governments. For that, Dulles would have to enlist the CIA. It was still a new agency, created in 1947 to replace the wartime Office of Strategic Services. Truman had used the CIA to gather intelligence and also to carry out covert operations, such as supporting anti-Communist political parties in Europe. Never, though, had he or Secretary of State Acheson ordered the CIA—or any other agency—to overthrow a foreign government.

Dulles had no such reservations. Two factors made him especially eager to use the CIA in this way. The first was the lack of alternatives. Long gone were the days when an American president could send troops to invade and seize a faraway land. A new world power, the Soviet Union, counterbalanced the United States and severely restricted its freedom to overthrow governments. An American invasion could set off a confrontation between superpowers that might spiral into nuclear holocaust. In the CIA, Dulles thought he might have the tool he needed, a way to shift the balance of world power without resorting to military force.

Calling on the CIA had another great attraction for Dulles. He knew he would work in perfect harmony with its director, because the director was his younger brother, Allen. This was the first and only time in American history that siblings ran the overt and covert arms of foreign policy. They worked seamlessly together, combining the diplomatic resources of the State Department with the CIA's growing skill at clandestine operations.

Before the coup could be set in motion, the Dulles brothers needed President Eisenhower's approval. It was not an easy sell. At a meeting of the National Security Council on March 4, 1953, Eisenhower wondered aloud why it wasn't possible "to get some of the people in these downtrodden countries to like us instead of hating us." Secretary of State Dulles conceded that Mossadegh was no Communist but insisted that "if he were to be assassinated or removed from power, a political vacuum might occur in Iran and the communists might easily take over." If that happened, he warned, "not only would the free world be deprived of the enormous assets represented by Iranian oil production and reserves, but ... in short order the other areas of the Middle East, with some Sixty percent of the world's oil reserves, would fall into Communist hands."

Dulles had two lifelong obsessions: fighting Communism and protecting the rights of multinational corporations. In his mind they were, as the historian James A. Bill has written, "interrelated and mutually reinforcing."

There is little doubt that petroleum considerations were involved in the American decision to assist in the overthrow of the Mossadegh government .... Although many have argued for America's disinterest in Iranian oil, given the conditions of glut that prevailed, Middle Eastern history demonstrates that the United States had always sought such access, glut or no glut .... Concerns about communism and the availability of petroleum were interlocked. Together, they drove America to a policy of direct intervention.

After the National Security Council meeting in March, planning for a coup began in earnest. Allen Dulles, in consultation with his British counterparts, chose a retired general named Fazlollah Zahedi as titular leader of the coup. Then he sent $1 million to the CIA station in Tehran for use "in any way that would bring about the fall of Mossadegh." John Foster Dulles directed the American ambassador in Tehran, Loy Henderson, to contact Iranians who might be interested in helping to carry out the coup.

Two secret agents, Donald Wilber of the CIA and Norman Darbyshire of the British Secret Intelligence Service, spent several weeks that spring in Cyprus devising a plan for the coup. It was unlike any plan that either country, or any country, had made before. With the cold calculation of the surgeon, these agents plotted to cut Mossadegh away from his people.

Under their plan, the Americans would spend $150,000 to bribe journalists, editors, Islamic preachers, and other opinion leaders to "create, extend and enhance public hostility and distrust and fear of Mossadegh and his government." Then they would hire thugs to carry out "staged attacks" on religious figures and other respected Iranians, making it seem that Mossadegh had ordered them. Meanwhile, General Zahedi would be given a sum of money, later fixed at $135,000, to "win additional friends" and "influence key people." The plan budgeted another $11,000 per week, a great sum at that time, to bribe members of the Iranian parliament. On "coup day," thousands of paid demonstrators would converge on parliament to demand that it dismiss Mossadegh. Parliament would respond with a "quasi-legal" vote to do so. If Mossadegh resisted, military units loyal to General Zahedi would arrest him.

"So this is how we get rid of that madman Mossadegh!" Secretary of State Dulles exclaimed happily when he was handed a copy of the plan.

Not everyone embraced the idea. Several CIA officers opposed it, and one of them, Roger Goiran, chief of the CIA station in Tehran, went so far as to quit. Neither of the State Department's principal Iran experts was even informed about the plot until it was about to be sprung. That was just as well, since State Department archives were bulging with dispatches from Henry Grady, who had been Truman's ambassador in Iran, reporting that Mossadegh "has the backing of 95 to 98 percent of the people of this country," and from Grady's boss, Undersecretary of State George McGhee, who considered Mossadegh "a conservative" and "a patriotic Iranian nationalist" with "no reason to be attracted to socialism or communism."

None of this made the slightest impact on Dulles. His deepest instinct, rather than any cool assessment of facts, told him that overthrowing Mossadegh was a good idea. Never did he consult with anyone who believed differently.

The American press played an important supporting role in Operation Ajax, as the Iran coup was code-named. A few newspapers and magazines published favorable articles about Mossadegh, but they were the exceptions. The New York Times regularly referred to him as a dictator. Other papers compared him to Hitler and Stalin. Newsweek reported that, with his help, Communists were "taking over" Iran. Time called his election "one of the worst calamities to the anti-communist world since the Red conquest of China."

To direct its coup against Mossadegh, the CIA had to send a senior agent on what would necessarily be a dangerous clandestine mission to Tehran. Allen Dulles had just the man in Kermit Roosevelt, the thirtyseven- year-old Harvard graduate who was the agency's top Middle East expert. Bya quirk of history, he was the grandson of President Theodore Roosevelt, who half a century earlier had helped bring the United States into the "regime change" era.

Roosevelt slipped into Iran at a remote border crossing on July 19, 1953, and immediately set about his subversive work. It took him just a few days to set Iran aflame. Using a network of Iranian agents and spending lavish amounts of money, he created an entirely artificial wave of anti-Mossadegh protest. Members of parliament withdrew their support from Mossadegh and denounced him with wild charges. Religious leaders gave sermons calling him an atheist, a Jew, and an infidel. Newspapers were filled with articles and cartoons depicting him as everything from a homosexual to an agent of British imperialism. He realized that some unseen hand was directing this campaign, but because he had such an ingrained and perhaps exaggerated faith in democracy, he did nothing to repress it.

"Mossadegh's avowed commitment to promoting and respecting political and civil rights and liberties, and allowing the due process of law to take its course, greatly benefited his enemies," the historian Fakhreddin Azimi wrote years later.

At the beginning of August, though, Mossadegh did take one step to upset the CIA's plan. He learned that foreign intelligence agents were bribing members of parliament to support a no-confidence motion against him, and to thwart them, he called a national referendum on a proposition that would allow him to dissolve parliament and call new elections. On this occasion he shaded his democratic principles, using separate ballot boxes for "yes" and "no" voters. The result was overwhelmingly favorable. His enemies denounced him, but he had won a round. Bribed members of parliament could not carry out the CIA's plan to remove him through a "quasi-legal" vote, since there no longer was a parliament.

Roosevelt quickly came up with an alternative plan. He would arrange for Mohammad Reza Shah to sign royal decrees, or firmans, dismissing Mossadegh from office and appointing General Zahedi as the new prime minister. This course could also be described as "quasi-legal," since under Iranian law, only parliament had the right to elect and dismiss prime ministers. Roosevelt realized that Mossadegh, who among other things was the country's best-educated legal scholar, would reject the firman and refuse to step down. He had a plan for that, too. A squad of royalist soldiers would deliver the firman, and when Mossadegh rejected it the soldiers would arrest him.

The great obstacle to this plan turned out to be the shah. He hated Mossadegh, who was turning him into little more than a figurehead, but was terrified of risking his throne by joining a plot. In a series of meetings held late at night in the backseat of a car parked near the royal palace, Roosevelt tried and failed to persuade the shah to join the coup. Slowly he increased the pressure. First he arranged to fly the shah's strong-willed twin sister, Ashraf, home from the French Riviera to appeal to him; she agreed to do so after receiving a sum of money and, according to one account, a mink coat. When that approach failed, Roosevelt sent two of his Iranian agents to assure the shah that the plot was a good one and certain to succeed. Still the shah vacillated. Finally, Roosevelt summoned General Norman Schwarzkopf, a dashing figure who had spent years in Iran running an elite military unit-and whose son would lead the Desert Storm invasion of Iraq four decades later-to close the deal.

The shah received Schwarzkopf in a ballroom at the palace, but at first refused to speak. Through gestures, he let his guest know that he feared that microphones were hidden in the walls or ceiling. Finally the two men pulled a table into the center of the room and climbed on top of it. In what must have been unusually forceful whispers, Schwarzkopf made clear that the power of both Britain and the United States lay behind this plot, and that the shah had no choice other than to cooperate. Slowly the shah gave in. The next day he told Roosevelt he would sign the (irmans, but only on condition that immediately afterward, he could fly to his retreat on the Caspian Sea.

"If by any horrible chance things go wrong, the Empress and I will take our plane straight to Baghdad," he explained.

That was not exactly a resounding commitment to the coup, but it was good enough for Roosevelt. He secured the (irmans and, on the afternoon of August 14, gave the one dismissing Mossadegh to an officer who was part of the plot, Colonel Nematollah Nassiri, commander of the Imperial Guard. Late that night, Nassiri led a squad of men to Mossadegh's house. There he told the gatekeeper that he needed to see the prime minister immediately.

Then, much to Nassiri's surprise, a company of loyalist soldiers emerged from the shadows, surrounded him, and took him prisoner. Mossadegh had discovered the plot in time. The man who was supposed to arrest him was himself arrested.

At dawn the next morning, Radio Tehran broadcast the triumphant news that the government had crushed an attempted coup by the shah and "foreign elements." The shah heard this news at his Caspian retreat, and reacted just as he had promised. With Empress Soraya at his side, he jumped into his Beechcraft and flew to Baghdad. There he boarded a commercial flight to Rome. When an American reporter asked him if he expected to return to Iran, he replied, "Probably, but not in the immediate future."

Roosevelt, however, was not so easily discouraged. He had built up a far-reaching network of Iranian agents and had paid them a great deal of money. Many of them, especially those in the police and the army, had not yet had a chance to show what they could do. Sitting in his bunker beneath the American embassy, he considered his options. Returning home was the obvious one. He even received a cable from his CIA superiors urging that he do so. Instead of obeying, he summoned two of his top Iranian operatives and told them he was determined to make another stab at Mossadegh.

These two agents had excellent relations with Tehran's street gangs, and Roosevelt told them he now wished to use those gangs to set off riots around the city. To his dismay, they replied that they could no longer help him because the risk of arrest had become too great. This was a potentially fatal blow to Roosevelt's new plan. He responded in the best tradition of secret agents. First he offered the two agents $50,000 to continue working with him. They remained unmoved. Then he added the second part of his deal: if the men refused, he would kill them. That changed their minds. They left the embassy compound with a briefcase full of cash and a renewed willingness to help.

That week, a plague of violence descended on Tehran. Gangs of thugs ran wildly through the streets, breaking shop windows, firing guns into mosques, beating passersby, and shouting "Long Live Mossadegh and Communism!" Other thugs, claiming allegiance to the self-exiled shah, attacked the first ones. Leaders of both factions were actually working for Roosevelt. He wanted to create the impression that the country was degenerating into chaos, and he succeeded magnificently.

Mossadegh's supporters tried to organize demonstrations on his behalf, but once again his democratic instincts led him to react naively. He disdained the politics of the street, and ordered leaders of political parties loyal to him not to join the fighting. Then he sent police units to restore order, not realizing that many of their commanders were secretly on Roosevelt's payroll. Several joined the rioters they were supposed to suppress.

Leaders of the Tudeh party, who had several hundred militants at their command, made a last-minute offer to Mossadegh. They had no weapons, but if he would give them some, they would attack the mobs that were trying to destroy his regime. The old man was horrified.

"If ever I agree to arm a political party," he told one Tudeh leader angrily, "may God sever my right arm!"

Roosevelt chose Wednesday, August 19, as the climactic day. On that morning, thousands of demonstrators rampaged through the streets, demanding Mossadegh's resignation. They seized Radio Tehran and set fire to the offices of a progovernment newspaper. At midday, military and police units whose commanders Roosevelt had bribed joined the fray, storming the foreign ministry, the central police station, and the headquarters of the army's general staff.

As Tehran fell into violent anarchy, Roosevelt calmly emerged from the embassy compound and drove to a safe house where he had stashed General Zahedi. It was time for the general to play his role as Iran's designated savior. He did so with gusto, riding with a group of his jubilant supporters to Radio Tehran and proclaiming to the nation that he was "the lawful prime minister by the Shah's orders." From there he proceeded to his temporary headquarters at the Officers' Club, where a throng of ecstatic admirers was waiting.

The day's final battle was for control of Mossadegh's house. Attackers tried for two hours to storm it but were met with withering machinegun volleys from inside. Men fell by the dozen. The tide finally turned when a column of tanks appeared, sent by a commander who was part of the plot. The tanks fired shell after shell into the house. Finally resistance from inside ceased. A platoon of soldiers gingerly moved in. Defenders had fled over a back wall, taking their deposed leader with them. The crowd outside surged into his house, looting it and then setting it afire.

No one was more amazed by this sudden turn of events than the shah. He was dining at his Rome hotel when news correspondents burst in to tell him the news of Mossadegh's overthrow. For several moments he was unable to speak.

"Can it be true?" he finally asked.

In the days that followed, the shah returned home and reclaimed the Peacock Throne he had so hastily abandoned. Mossadegh surrendered and was placed under arrest. General Zahedi became Iran's new prime minister.

Before leaving Tehran, Roosevelt paid a farewell call on the shah. This time they met inside the palace, not furtively in a car outside. A servant brought vodka, and the shah offered a toast.

"lowe my throne to God, my people, my army-and to you," he said.

Roosevelt and the shah spoke for a few minutes, but there was little to say. Then General Zahedi, the new prime minister, arrived to join them. These three men were among the few who had any idea of the real story behind that week's tumultuous events. All knew they had changed the course of Iranian history.

"We were all smiles now," Roosevelt wrote afterward. "Warmth and friendship filled the room."

"Yes, my sin—my greater sin . . . and even my greatest sin is that I nationalized Iran's oil industry and discarded the system of political and economic exploitation by the world's greatest empire . . . This at the cost to myself, my family; and at the risk of losing my life, my honor and my property . . . With God's blessing and the will of the people, I fought this savage and dreadful system of international espionage and colonialism." (December 19, 1953)

In light of all the questionable, contradictory, and devious statements which emanated at times from John Foster Dulles, Kermit Roosevelt, Loy Henderson and other American officials, what conclusions can be drawn about American motivation in the toppling of Mossadegh? The consequences of the coup may offer the best guide.

For the next 25 years, the Shah of Iran stood fast as the United States' closest ally in the Third World, to a degree that would have shocked the independent and neutral Mossadegh. The Shah literally placed his country at the disposal of US military and intelligence organizations to be used as a cold-war weapon, a window and a door to the Soviet Union—electronic listening and radar posts were set up near the Soviet border; American aircraft used Iran as a base to launch surveillance flights over the Soviet Union; espionage agents were infiltrated across the border; various American military installations dotted the Iranian landscape. Iran was viewed as a vital link in the chain being forged by the United States to "contain" the Soviet Union. In a telegram to the British Acting Foreign Secretary in September, Dulles said: "I think if we can in coordination move quickly and effectively in Iran we would close the most dangerous gap in the line from Europe to South Asia." In February 1955, Iran became a member of the Baghdad Pact, set up by the United States, in Dulles's words, "to create a solid band of resistance against the Soviet Union".

One year after the coup, the Iranian government completed a contract with an international consortium of oil companies. Amongst Iran's new foreign partners, the British lost the exclusive rights they had enjoyed previously, being reduced now to 40 percent. Another 40 percent now went to American oil firms, the remainder to other countries. The British, however, received an extremely generous compensation for their former property.

In 1958, Kermit Roosevelt left the CIA and presently went to work for Gulf Oil Co., one of the American oil firms in the consortium. In this position, Roosevelt was director of Gulfs relations with the US government and foreign governments, and had occasion to deal with the Shah. In 1960, Gulf appointed him a vice president. Subsequently, Roosevelt formed a consulting firm, Downs and Roosevelt, which, between 1967 and 1970, reportedly received $116,000 a year above expenses for its efforts on behalf of the Iranian government. Another client, the Northrop Corporation, a Los Angeles-based aerospace company, paid Roosevelt $75,000 a year to aid in its sales to Iran, Saudi Arabia and other countries.

Another American member of the new consortium was Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey (now Exxon), a client of Sullivan and Cromwell, the New York law firm of which John Foster Dulles had long been the senior member. Brother Allen, Director of the CIA, had also been a member of the firm. Syndicated columnist Jack Anderson reported some years later that the Rockefeller family, who controlled Standard Oil and Chase Manhattan Bank, had "helped arrange the CIA coup that brought down Mossadegh". Anderson listed a number of ways in which the Shah demonstrated his gratitude to the Rockefellers, including heavy deposits of his personal fortune in Chase Manhattan, and housing developments in Iran built by a Rockefeller family company.

The standard "textbook" account of what took place in Iran in 1953 is that— whatever else one might say for or against the operation—the United States saved Iran from a Soviet/Communist takeover. Yet, during the two years of American and British subversion of a bordering country, the Soviet Union did nothing that would support such a premise. When the British Navy staged the largest concentration of its forces since World War II in Iranian waters, the Soviets took no belligerent steps; nor when Great Britain instituted draconian international sanctions which left Iran in a deep economic crisis and extremely vulnerable, did the oil fields "fall hostage" to the Bolshevik Menace; this, despite "the whole of the Tudeh Party at its disposal" as agents, as Roosevelt put it. Not even in the face of the coup, with its imprint of foreign hands, did Moscow make a threatening move; neither did Mossadegh at any point ask for Russian help.

One year later, however, the New York Times could editorialize that "Moscow ... counted its chickens before they were hatched and thought that Iran would be the next 'People's Democracy." At the same time, the newspaper warned, with surprising arrogance, that "underdeveloped countries with rich resources now have an object lesson in the heavy cost that must be paid by one of their number which goes berserk with fanatical nationalism."

A decade later, Allen Dulles solemnly stared that communism had "achieved control of the governmental apparatus" in Iran. And a decade after that, Fortune magazine, to cite one of many examples, kept the story alive by writing that Mossadegh "plotted with the Communist party of Iran, the Tudeh, to overthrow Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlevi and hook up with the Soviet Union."

And what of the Iranian people? What did being "saved from communism" do for them? For the preponderance of the population, life under the Shah was a grim tableau of grinding poverty, police terror, and torture. Thousands were executed in the name of fighting communism. Dissent was crushed from the outset of the new regime with American assistance. Kennett Love wrote that he believed that CIA officer George Carroll, whom he knew personally, worked with General Farhat Dadsetan, the new military governor of Teheran, "on preparations for the very efficient smothering of a potentially dangerous dissident movement emanating from the bazaar area and the Tudeh in the first two weeks of November, 1953".

1. A helpful note from Noam Chomsky: Recall that Israel was closely allied to Iran prior to the fall of the Shah. The nature of this alliance was revealed in part after the Shah's fall by discussion in the Israeli press, particularly, the account by former Israeli Ambassador Uri Lubrani, who reports that "the entire upper echelon of the Israeli political leadership" visited the Shah’s Iran, including David Ben-Gurion, Golda Meir, Abba Eban, Yitzhak Rabin, Yigal Allon, Moshe Dayan, and Menachem Begin, and who describes the warm relations that developed between Israel's Labor leaders and the Shah's secret police (SAVAK), who hosted these visits, taking time off from torturing prisoners.The notorious Iranian secret police, SAVAK, created under the guidance of the CIA and Israel1, spread its tentacles all over the world to punish Iranian dissidents. According to a former CIA analyst on Iran, SAVAK was instructed in torture techniques by the Agency2. Amnesty International summed up the situation in 1976 by noting that Iran had the "highest rate of death penalties in the world, no valid system of civilian courts and a history of torture which is beyond belief. No country in the world has a worse record in human rights than Iran."

When to this is added a level of corruption that "startled even the most hardened observers of Middle Eastern thievery", it is understandable that the Shah needed his huge military and police force, maintained by unusually large US aid and training programs, to keep the lid down for as long as he did. Said Senator Hubert Humphrey, apparently with some surprise:

Do you know what the head of the Iranian Army told one of our people? He said the Army was in good shape, thanks to U.S. aid—it was now capable of coping with the civilian population. That Army isn't going to fight the Russians. It's planning to fight the Iranian people.

Where force might fail, the CIA turned to its most trusted weapon—money. To insure support for the Shah, or at least the absence of dissent, the Agency began making payments to Iranian religious leaders, always a capricious bunch. The payments to the ayatollahs and mullahs began in 1953 and continued regularly until 1977 when President Carter abruptly halted them. One "informed intelligence source" estimated that the amount paid reached as much as $400 million a year; others thought that figure too high, which it certainly seems to be. The cut-off of funds to the holy men, it is believed, was one of the elements which precipitated the beginning of the end for the King of Kings

The notorious Iranian security service, SAVAK, which employed

torture routinely, was created under the guidance of the CIA and

Israel in the 1950s.According to a former CIA analyst on Iran, Jesse

J. Leaf, SAVAK was instructed in torture techniques by the Agency.

After the 1979 revolution, the Iranians found CIA film made for

SAVAK on how to torture women.