James R. Bradley, a slave in the Arkansas Territory who worked until he was able to buy his way into freedom, wrote this damning account1 of his experience of slavery to Lydia Maria Child, the abolitionist author the editor of an antislavery journal, The Oasis.

From Voices of A People's History, edited by Zinn and Arnove

Dear Madam:

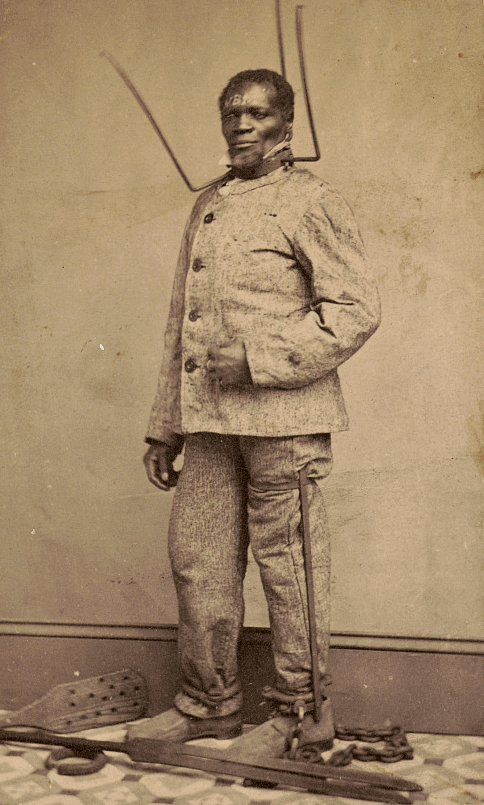

I am now going to try to write a little account of my life as nearly as I can remember. It makes me sorrowful to think of my past days. They have been very dark and full of tears. I always longed and prayed for liberty. I sometimes hoped I should get it and then I would think and pray and study out some way to earn money enough to buy myself by working nights, and then something would fall out and all my hopes would die and it seemed as though I must live and die a slave without anyone to pity me. But I will begin as far back as I can remember. When I was between two and three years old the soul destroyers tore me from my tender mothe[r's] arms somewhere in Africa far back from the sea. They carried me along [a long] distance to the ships. I looked back and wept all the way. The ship was full of men and women loaded down with chains. As I was so small they let me run about on deck. After many long days they brought me to Charles town [South Carolina]. Then a slave holder bought me and took me up into Pendleton county. I suppose that I stayed with him about six months. Then he sold me to a man whose name was Bradley. Ever since then I have been called by that name. This man was called a wonderfully kind master and he was more kind than most masters. He gave me enough to eat and did not beat me so much as masters g[enera]lly do. But all that was nothing to me. I spent many sleepless nights and bathed my face in tears because I was a slave. I... groaned for liberty....

I have said a good deal about my desire for liberty. How strange it is it that any body should believe that a human being could be a slave and feel contented. I don't believe there ever was a slave who did not long for liberty. I know very well that slaveholders take a great deal of pain to make the people of free states believe that this class are happy and contented—and I kn[o]w too that I never knew a slave—no matter how well he was treated—that did not long to be free. There is one thing about this that people of free states don't understand. When they talk with slaves and ask them if they don't want their liberty and if they wouldn't like to be free like the white men—they say no—and very likely they will go on and say that they wouldn't leave their master for the world, when at the same time they have [been] along time laying plans to get free and desire liberty more than anything else in the world. The truth is and every slave knows it—if he should say he wanted to be free and should show any weariness and discontent because he is a slave he is sure to be treated harsher and worked harder for it. So they are always very careful not to show any weariness and particularly when they are asked questions about freedom by white men. When the slaves are together by themselves alone, they are always talking about liberty, liberty is the great thought and feeling that fills the mind full all the time. I could say a great many things more but as you requested in your letter to my dear friend Mr. [Theodore] Weld that I would write a "short account'' of my life I am afraid I have written too much already and will say but a few words more. My heart is full and flows over when I hear what is doing for the poor broken hearted slave and free man of color. God will help those who take the part of the oppressed. Yes blessed be his name he will s[u]rely do it. Dear Madam I do not know you personally but I have seen your book on slavery and have read much about you, and I do hope to meet you at the resurrection of the Just. I thank God he has given to the poor bleeding slave and to all the oppressed colored race such a dear friend. May God graciously preserve you—dear Madam, and bless your labors and make you great in this holy cause until you see all the walls of prejudice broke down and all the chains of slavery broken to pieces and all of every color sitting down—together at Jesus' feet, a band of brethren speaking kind words and looking upon each others faces in love and as they expect to love each other and live together in heaven, be willing to love each other and live together on earth.

Footnotes

1 James R. Bradley, Letter to Lydia Maria Child (June 3. 1834). In C. Peter Ripley, ed.. The Black Abolitionist Papers, Volume III: The United States. 1830-1846 (Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), pp. 136-37, 139-40. From the Anti-Slavery Collection, Boston Public Library, Boston, Massachusetts. All errors are in original.