|

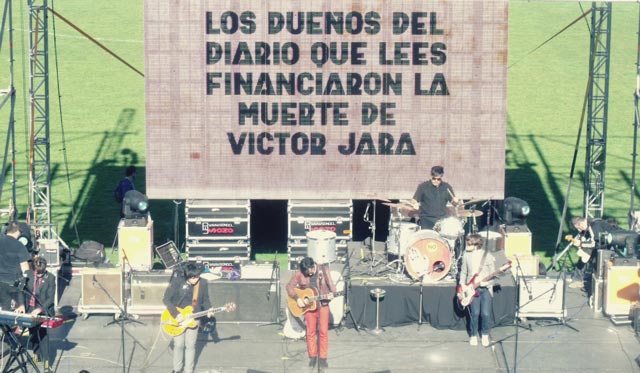

Contemporary Chilean band Los Bunkers perform with a backdrop reading "The owners of the newspaper you read financed the death of Victor Jara." |

|

"I don't see why we need to stand by and watch a country go communist due to the irresponsibility of its own people. The issues are much too important for the Chilean voters to be left to decide for themselves." — Henry Kissinger "Not a nut or bolt shall reach Chile under Allende. Once Allende comes to power we shall do all within our power to condemn Chile and all Chileans to utmost deprivation and poverty." — Edward M. Korry, U.S. Ambassador to Chile, upon hearing of Allende's election. "Make the economy scream [in Chile to] prevent Allende from coming to power or to unseat him" — Richard Nixon, orders to CIA director Richard Helms on September 15, 1970 "It is firm and continuing policy that Allende be overthrown by a coup. It would be much preferable to have this transpire prior to 24 October [1970] but efforts in this regard will continue vigorously beyond this date. We are to continue to generate maximum pressure toward this end, utilizing every appropriate resource. It is imperative that these actions be implemented clandestinely and securely so that the USG and American hand be well hidden..." — A communique to the CIA base in Chile, issued on October 16, 1970

|